- Home

- Sean B. Carroll

Brave Genius Page 28

Brave Genius Read online

Page 28

The end of the war in the Pacific three months later brought more relief but also new anxieties, as it was precipitated by the dropping of atomic bombs. Camus was understandably alarmed: “Given the terrifying prospects that mankind now faces, we see even more clearly than before that the battle for peace is the only battle worth fighting. This is no longer a prayer but an order that must make its way up from peoples to their governments: it is the order to choose once and for all between hell and reason.”

By the end of the war, and by virtue of scores of editorials, the reprinting of The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus, the publication of his Letters to a German Friend, the remounting of his play The Misunderstanding, and the publication of Caligula, Camus was firmly established (along with his friend Sartre) as a leading public intellectual in France. Even his fiercest critics acknowledged that Camus was “the French editorialist who is most widely read in the world.”

But Camus aspired to different goals. As the full magnitude of the war’s toll came to light—tens of millions of soldiers and civilians killed in battle, millions more exterminated or nearly so in camps, vast populations left homeless and hungry, much of Europe in ruins, and the advent of new weapons capable of leveling entire cities—his audiences struggled to grasp the catastrophe and despaired for the future. Having justified resistance as a reason for dying, the outstanding challenge was to help his readers find good reasons for living.

CHAPTER 18

SECRETS OF LIFE

There is nothing over which a free man ponders less than death; his wisdom is to meditate not on death but on life.

—SPINOZA, Ethics

(Quoted by Erwin Schrödinger in the preface to What Is Life?)

AS GERMANY WAS DEFEATED, MORE THAN 2.4 MILLION FRENCH prisoners of war, STO workers, political prisoners, and racial deportees began to return from the former Reich—most of the latter in shocking physical condition and with unimaginable, horrifying stories to tell. Camus and Combat celebrated Claude Bourdet’s rescue from Buchenwald and Jacqueline Bernard’s return from Ravensbrück. Camus and Pia went immediately to see Bernard and said, “Combat is waiting for you, your office is ready, when you wish.” Marcel Prenant, Monod’s former FTP chief, returned in early June, weighing just ninety pounds after barely surviving a typhus-induced coma. Odette’s brother Étienne returned home as well. However, tens of thousands of Frenchmen and Frenchwomen, among them Bernard’s brother Jean-Guy and Monod’s friend Raymond Croland, did not return from the camps.

French soldiers also started coming home. After Germany’s surrender, the French Army’s mission turned from combat to occupation. Monod had no interest in that role, nor any desire to remain in uniform. As six of his first seven years of marriage and all of the twins’ first six years of childhood had been occupied by war, he was eager to be demobilized and to return to his family and scientific work. While he had hoped to be released at the end of May, his papers would not be signed until the beginning of July.

After returning to Paris, Monod wanted only to go back to the lab and to think about nothing else. He consciously “drew a curtain over the memory of wartime.” He started to pick up where his work had left off a year and a half earlier. He returned to the Sorbonne, but not for long. That fall, Lwoff invited Monod to join his Department of Microbial Physiology at the Pasteur Institute as a laboratory head. Monod accepted, and went about setting up his lab and catching up on what had transpired while he had been away from biology.

He had learned of one major advance while still in the Army. Before his release, he happened across several back issues of the scientific journal Genetics in, of all places, an American Army bookmobile. In the November 1943 issue, an article by Salvador Luria and Max Delbrück seized his attention. The two authors were both refugees from Europe working in the United States: Luria had fled Mussolini’s Italy, and Delbrück had left Hitler’s Germany before the war. The duo showed elegantly and convincingly that bacteria spontaneously acquired heritable mutations. Specifically, they found that bacteria acquired resistance to infection with bacterial viruses called bacteriophage (literally “bacteria-eaters”). The paper confirmed the interpretation that Monod and Alice Audureau had reached in early 1944 but had not yet published: that the appearance of lactose-utilizing E. coli colonies in strains that could not utilize lactose were genetic mutants.

Up until the publication of the Luria-Delbrück paper, there was considerable confusion concerning the properties of bacteria and much doubt about their usefulness as genetic models in biology. Indeed, in what would be one of the most influential books in evolutionary biology (Evolution: The Modern Synthesis, published in 1942), Julian Huxley (grandson of zoologist and Darwin apostle Thomas Henry Huxley) considered bacteria irrelevant to processes in more complex organisms: “They have no genes in the sense of … hereditary substance … Occasional ‘mutations’ occur we know, but there is no ground for supposing that they are similar in nature to those of higher organisms … We must, in fact, expect that the processes of variation, heredity, and evolution in bacteria are quite different from the corresponding processes in multicellular organisms.” If these statements were true, then Monod’s own work on enzyme adaptation would be of no general importance or utility.

Huxley’s claims were not the fault of any particular ignorance on his part—he did not work in the field himself. Rather, it was a reflection of the general ignorance in biology concerning the fundamental nature of heredity, and of the substances that endowed life with properties that distinguished it from nonliving matter. Indeed, so little was known at the outset of World War II about the nature of life that notions of vitalism—the idea that life emerges from some substance or force (a “vital principle”) beyond the physical and chemical laws that govern inanimate matter—still lurked, at least among some physicists.

The murky state of knowledge prompted the Nobel Prize–winning Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger to ask “What is life?” in a short book of that title. Written in 1943–44 in Dublin, where Schrödinger had retreated after Hitler rose to power, What Is Life? had one of the celebrated fathers of quantum mechanics asking whether biology was also reducible to the sorts of mechanics that governed inanimate matter. Schrödinger posed one question at the outset: “How can the events in space and time which take place within the spatial boundary of a living organism be accounted for by physics and chemistry?”

His “preliminary answer” was: “The obvious inability of present-day physics and chemistry to account for such events is no reason at all for doubting that they can be accounted for by those sciences.”

Schrödinger paid particular attention to the mystery of heredity. Thanks especially to the work of T. H. Morgan’s group, the very lab Monod had visited at Caltech before the war, genes were understood to be discrete entities on chromosomes, but their physical structure and chemical makeup were unknown. From the point of view of physics, the existence and properties of genes posed several perplexing problems. It was certain that genes were made up of atoms of some kind, but how could the arrangement of atoms in genes specify the characteristics of an organism—eye color, hair texture, bone length, and so on? Moreover, what properties of genes endowed them with the dual behavior of stability (such that traits were passed faithfully from one generation to the next and the next and so on) and of mutability (such that changes in genes occurred, and those were then also passed from generation to generation)? Schrödinger speculated that genes were some kind of “aperiodic solid” that contained some version of an “elaborate code-script” that specified all of the future development of the organism. How genes worked, how information contained within that solid specified an organism, and how that information was transmitted or altered through time were thus the central mysteries of biology and of what would become known as molecular biology. (For further details or an overview of the science in this book, see Appendix.)

Schrödinger’s book would help convince a number of physicists to turn to biology,

Francis Crick among them, and a number of young biologists—including James Watson—to pursue genetics (instead of ornithology, in Watson’s case).

Schrödinger’s book was mostly conjecture. Biologists had to find ways to crack open the gene the way physicists had the atom. For Monod, the Luria-Delbrück paper established bacterial genetics, and thus the foundation for asserting that the great mysteries of heredity were accessible in simple organisms that grew quickly and were easy to work with. Moreover, because of the mutants that he and Alice Audureau had isolated, he had a finger hold on a genetically controlled trait—bacterial growth on the sugar lactose—that could offer a path into understanding how genes work.

To get his lab rolling at the Pasteur Institute, he needed to hire some staff. Madeleine Vuillet, a recent chemistry graduate of a vocational school, heard about an opening and went to present herself to Dr. Monod. As she sat on a stool in a tiny laboratory in the attic of the Pasteur, a handsome young man dressed in canvas pants and an open-collared sport shirt came in whistling. She ignored him, until he introduced himself as Jacques Monod. Vuillet was flustered, as she had thought that all scientists were “strict and severe-looking old gentlemen.”

As the interview progressed, Vuillet wondered what she was doing there. She admitted that she knew very little organic chemistry, let alone microbial physiology. Monod was not discouraged. He told her, “At any rate, I prefer that you know nothing, because no school could teach you what we are going to need: I am in search of the secret of life.”

BEYOND NIHILISM

As Monod resumed his research, Camus continued on his quest for the philosophical secrets of life. And the secret for Camus, living in a profoundly traumatized world in which life had been devalued and peace appeared very fragile, was how to move beyond the nihilism of the times and find meaning in one’s earthbound life span. While his editorials had occasionally touched upon these subjects, such weighty matters required more extensive and artful examination. For almost exactly one year, Camus had been so immersed in Combat that he had had little time for his own projects. On September 1, 1945, Camus stepped back from his daily editorial role in order to devote more time to his writing, as well as to his new family life: the Camus twins, Catherine and Jean, were born on September 5.

Two questions dominated Camus’s thinking, his notebooks, conversations, interviews, and speeches: How could individuals find some meaning in their existence? And how could another cataclysm be prevented?

It was understandable and easy to be pessimistic in responding to either question. Two world wars in fewer than thirty years was hardly a basis for optimism. The magnitude of the most recent suffering and death shattered faith for many who asked “Where was God?” and received no satisfactory answer. And for those who did not believe in God in the first place, more than fifty million dead was their proof.

Nihilism, the view that life was meaningless and worthless, followed readily from this loss of faith for many people. But not for Camus. In The Myth of Sisyphus, he had rejected nihilism and answered affirmatively the question of whether life is worth living. He viewed nihilism as the central philosophical and ethical challenge of the time, indeed of the twentieth century, and sought a variety of means to counter it. As he stepped away from Combat, he returned part-time to the publisher Gallimard as a reader. Gallimard put him in charge of a series that aimed to capitalize on his fame to draw new writers to the publishing house. The series, to be called Espoir (Hope), was to bear Camus’s name as editor and the back cover of each book would carry a common statement of purpose crafted by Camus: “We are living in nihilism … We shall not get out of it by pretending to ignore the evil of our time or by deciding to deny it. The only hope is to name it, on the contrary, and to inventory it to discover the cure for the disease … Let us thus recognize that this is a time for hope, even if it is a difficult hope.”

For Camus, meaning came from struggle, from revolt. He had already put this philosophy into words in The Myth of Sisyphus: “Revolt gives life its value.” Now it was time to finally put that philosophy into images, for, as Camus had noted years earlier: “feelings and images multiply a philosophy by ten.” His unfinished novel The Plague, which he had begun three years earlier as the first element of his “cycle” on revolt, would be his vehicle. Camus’s challenge was to create the images and characters in his fictional tale that would evoke the images and feelings of the Occupation and the Resistance with which he hoped all of France could identify.

Among the most resonant images of the novel would be the dead rats, signs of a threat to which no one at first paid attention; the closing of the city gates that cut off the town’s inhabitants from loved ones and created a profound sense of separation and exile; the voluntary sanitary squads that bravely risked their lives to fight the plague; the isolation camp in a municipal stadium where afflicted persons were quarantined; and, finally, the joyous reopening of the gates, the ringing of church bells, and the relighting of the streets once the plague was suppressed.

The protagonists of the story, through their courage and solidarity in doing what must be done to combat the plague, would gradually reveal Camus’s philosophy of revolt. In a phrase that could have been lifted from a pre-liberation Combat editorial, after the plague was declared and the gates ordered closed, the narrator states: “From now on, it can be said that plague was the concern of all of us.” The principal characters included Dr. Bernard Rieux, who first identifies the disease, warns the authorities, and works to combat it throughout the epidemic; Joseph Grand, a modest town clerk who is “the true embodiment of the quiet courage that inspired the sanitary groups”; Raymond Rambert, a visiting journalist who, like Camus in Le Panelier, becomes trapped in the city, is separated from his wife, and eventually joins the fight; Jean Tarrou, who organizes teams of volunteers; Father Paneloux, a Jesuit priest who interprets the plague as “the flail of God” and tells his fellow citizens, “Calamity has come on you … and, my brethren, you deserved it”; and Joseph Cottard, who takes advantage of the plague to become a smuggler and black-marketeer.

It would take Camus all of 1946 to complete and edit the novel. His routine was generally to write at home in the mornings, then to go to his Gallimard office after lunch to review manuscripts, to read and dictate his correspondence, and to receive visitors. In the evenings, he would socialize with friends such as Sartre and de Beauvoir, meeting them for a drink at one of the cafés on Saint-Germain-des-Prés, then perhaps going to dinner at a bistro and sometimes to another café for a nightcap, or more.

At the time, Sartre was in the process of launching a new literary journal, Les Temps Modernes (Modern Times). He penned the review’s manifesto in its inaugural issue, which was to publish “engaged literature”—writings that were socially relevant and not merely art for art’s sake. Several of Camus’s comrades joined the editorial board, but Camus declined Sartre’s invitation on account of his many commitments. The two men were often seen together in the Saint-Germain neighborhood, and the press took an interest in the lifestyles of Paris’s famous thinkers. In the public’s mind, Sartre’s and Camus’s respective works and perspectives became merged under one label: existentialism.

A once obscure and technical philosophical term, existentialism was moving from a small circle of intellectuals into popular culture—so much so, Sartre thought, that it was in danger of losing its meaning. He clarified the principles of existential philosophy in a speech in the fall of 1945, the first being “Man is nothing else but that which he makes of himself.” Sartre explained that existentialism “places the entire responsibility for [man’s] existence squarely upon his own shoulders.” There was no determinism, no such thing as human nature, no divine guidance or intention. Humans came into the world neither evil nor good, neither heroes nor cowards; all people were free to choose, and were defined not by their hopes or wishes but by their actions.

Existentialism’s message of individual freedom and self-determination struck a chord i

n the atmosphere of post-liberation France. After the failures of governments and religious institutions to prevent the war, after years of the empty nationalist clichés of Pétainism, and after the defeat of Fascism, existentialism suggested a way to begin rebuilding society from a clean slate—by rejecting conventions and authority and empowering the individual.

Both Sartre and Camus were constantly in demand for their views, and not only in France. In early 1946, Camus was invited by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs to undertake an extended visit to New York. It was a perk for prominent French citizens to promote France’s image abroad, and the timing happened to coincide with the upcoming publication of the English translation of The Stranger. Camus took along his working manuscript of The Plague.

The New York press and francophiles all over the East Coast were eager to hear more from this celebrated young author and Resistance journalist whom the New York Herald Tribune pronounced “The Boldest Writer in France Today” and the New York Times consecrated the “Apostle of Post-Liberation France.” The Times went on to say:

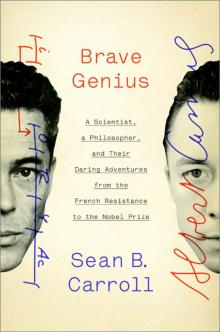

Brave Genius

Brave Genius