- Home

- Sean B. Carroll

Brave Genius Page 27

Brave Genius Read online

Page 27

Monod and the other officers assembled and stood at attention at the top of the stairs. The general entered the great hallway, strode up the steps, and then shook hands with each one of them.

A LITTLE WHILE later, the FFI officers moved to make room for de Gaulle and his staff. Noufflard went back to gather her belongings from Napoleon’s mother’s bedroom. She noticed that someone else’s luggage had already been moved inside; it bore the inscription COLONEL CHARLES DE GAULLE.

AT LAST, MONOD and Noufflard could enjoy a free Paris on a perfect, beautiful, clear summer night. Monod commandeered a car, upon which he and Noufflard fixed a small tricolor flag that had the Croix de Lorraine and the letters “FFI” embroidered on it, and they went for a celebratory drive. The car’s exhaust pipe was broken, so it made a very loud racket, but they ignored it as they sped through the streets enjoying their first ride in years. They cruised past burned-out German vehicles, trucks carrying FFI men, and throngs of joyous Parisians. They reached the Place de l’Étoile near sunset, where they saw their first American tanks and soldiers who had gathered around the Arc de Triomphe.

Darkness fell.

Then, suddenly, the city lit up. All over Paris, streetlights and monuments that had been dark for almost six years, since September 3, 1939, flashed back to life. Paris’s engineers and electricians had managed to summon enough power to relight Sacré-Coeur, Les Invalides, Notre-Dame, and the Eiffel Tower, from the top of which the French tricolor now flew for all to see.

On this first evening of freedom, the happiest in all of her glorious history, Paris was once again la plus belle ville du monde.

Combat issue number 63, August 25, 1944. The headline heralds the arrival of French troops in the capital. Camus’s anonymous editorial begins at the far left: “La nuit de la verité” (“The night of truth”). (Author’s collection)

Part Three

Secrets of Life

GENIUS IS TALENT SET ON FIRE BY COURAGE.

—HENRY VAN DYKE, THE FRIENDLY YEAR

Camus at Combat shortly after the liberation of Paris. Camus is at left; André Malraux is at right, wearing a beret. (Rue des Archives/The Granger Collection, New York)

CHAPTER 17

THE TALK OF THE NATION

The first thing for a writer to learn is the art of transposing what he feels into what he wants to make others feel.

—ALBERT CAMUS, Notebooks, 1942–1951

THE DAYS FOLLOWING THE LIBERATION WERE EUPHORIC.

The first full day of Paris’s freedom was celebrated by de Gaulle triumphantly parading down the Champs-Élysées from the Arc de Triomphe, with he, Leclerc, and Parodi preceding columns of French and Allied troops. The next morning’s issue of Combat accurately proclaimed: “All Paris in the Street to Cheer de Gaulle.”

It was also a time of revelations, when aliases and anonymity were dropped, and true identities were revealed. The same issue of the newspaper named the men behind Combat for the first time. A small notice after the editorial stated: “Albert CAMUS, Henri FREDERIC, Marcel GIMONT, Albert OLIVIER, and Pascal PIA actually write ‘Combat,’ after having written it in clandestinity.”

Camus perceived that it was a critical moment for the press—“a unique opportunity to create a public spirit and to rise to the level of the country at large.” Ever since that first meeting in his studio in July, planning for the public issuance of Combat, Camus had anticipated the role the newspaper would play in shaping the public discourse about the direction France would take once liberated. On the eve of liberation, he wrote: “The Paris that is fighting tonight wants to assume command tomorrow. Not for the sake of power but for the sake of justice, not for political reasons, but for moral ones, not to dominate their country but to ensure its grandeur.”

It was, Camus would say, a time of danger and hope. Danger because France’s economy was in ruins, its farms had no machinery, Germany was not yet defeated, and its army had no arms (except those given to it); hope because freedom had been regained, and if it learned from its very painful and costly lessons, there was the prospect of the rebirth of a greater France. In the days following liberation, Camus seized the platform that Combat provided to articulate his and his comrades’ highest ideals, to raise readers’ hopes, to warn them of dangers, and to criticize those who had not or were not living up to their duty. Some of his first remarks were directed at the press, which served both as a statement of his paper’s aspirations and a critique of those who were returning to bad habits. In his signed editorial “Critique of the New Press,” published in the first week after liberation, Camus expressed the hope that he and his peers, “who had braved mortal dangers for the sake of a few ideas they held dear, would find a way to give their country the press it deserved and no longer had.” He dismissed the prewar press as one that had “forfeited its principles and its morals” and whose “hunger for money and indifference to grandeur” had no goal beyond enhancing the power of a few. Such low aims, Camus asserted, prepared the way for the collaborationist press of the Occupation.

The common desire of the underground Resistance press, Camus believed, was to express “a tone and a truth that would allow the public to discover what was best in itself.” Camus exhorted his peers to recommit to this “tone,” and to create a press “that is clear and virile and written in a decent style.” He reminded them: “When you know, as we journalists have known these past four years, that writing an article can land you in prison or get you killed, it is obvious that words have value and need to be weighed carefully.”

Camus urged his colleagues “to write carefully without ever losing sight of the urgent need to restore to the country its authoritative voice. If we see to it that voice remains one of vigor rather than hatred, of proud objectivity and not rhetoric, of humanity rather than mediocrity, then much will be saved from ruin, and we will not have forfeited our right to our nation’s esteem.”

With the debris from the battle of Paris still littering the streets, and while the FFI and civilian losses were still being counted, Camus was exhorting the press to lead the nation away from its most base reactions to four years of oppression and toward the goal of making a new democracy in France. Camus hoped to influence, or at least to admonish, those newspapers that “seek to please when they ought simply to enlighten” or those that “seek to inform their readers quickly rather than to inform them well,” for he noted: “The truth is not the beneficiary in this setting of priorities.”

Camus, of course, had to practice what he preached. To enrich Combat’s tone and style, he commissioned Jean-Paul Sartre to write a series of articles on the liberation of Paris, then sent him on a long tour of the United States as a correspondent. And day after day, Parisians read and discussed Camus’s editorials that spoke repeatedly of truth, courage, character, liberty, and democracy. Beyond establishing a nobler press, Camus largely focused on a few dominant issues. Foremost among these was the question of what kind of nation was to be rebuilt. For Camus, the crux of the issue was reconciling justice and freedom. He wrote: “To ensure that life is free for each of us and just for all is the goal we must pursue … Indeed, nothing else is worth living and fighting for in today’s world.”

A second major concern was the matter of who was fit to lead France. He castigated any thought of reinserting “experienced men” from previous regimes (Vichy or the Third Republic), as they had led the country to ruin, or were at the very least guilty of not having done enough to save it. He declared: “The affairs of this country should be managed by those who paid and answered for it.”

A particularly sensitive issue was the recognition of de Gaulle’s provisional government (GPRF) by the Allies. Britain and the United States were keenly aware that, despite talk of a united France, de Gaulle, the various parties of the Resistance, and the Communists viewed one another with suspicion. British and American leaders harbored reservations about each faction and were tempted to play favorites. In four editorials, Camus pressed the case for r

ecognition of the provisional government as the authority within France, and cautioned against meddling in what he insisted were France’s internal affairs. “If our American friends want a strong and united France, dividing France from outside is not a good way to go about it,” he wrote. Camus, who had devoted an entire editorial to paying respect to Britain’s “inner strength and tranquil courage” and her defense of freedom during the war, made a simple, direct case: “We have lost many things in this war, but not so much that we are willing to resign ourselves to begging for what is rightfully ours … We want to be able to love our friends freely and to prove that there is no bitterness in our gratitude. We believe that we are not asking for much. And if that is still not convincing, then we ask that steps be taken to ease our difficult task in view of our long history of teaching the very name of freedom to a world that knew nothing about it.”

While elections would have been the preferred means of settling the issue, no vote was initially possible given the country’s disarray. Moreover, some argued, including Camus, that it would be unfair and disrespectful to the more than two million POWs, deportees, and workers outside of the country who were unable to vote. Days after his fourth editorial on the matter, the American, British, Soviet, and Canadian governments recognized the GPRF.

Camus had urged the press to provide the country “with a language that will induce it to listen.” And listen to Camus they did. The novelist-playwright turned editorialist now had an audience in the hundreds of thousands. Writer Raymond Aron, who had joined de Gaulle’s Free French, edited its magazine during the war, and would later join Combat as an editorialist, remarked that readers of Camus’s editorials had formed the habit of getting their daily thought from him. Combat often sold out, and Camus’s editorials were the talk of Paris—both on the street as well as among the intelligentsia.

After the liberation, Camus’s private life also underwent a transformation. Francine returned to Paris from Algeria in October, and she was pregnant by December—with twins. Maria Casarès chose to exit the scene.

THE AMALGAMATION

Five years after war was first declared, and after more than four years of occupation, it was understandable that in the joy of liberation most Parisians were eager to reunite their families and to return to some semblance of normal life. Indeed, by October, the Monods were all back together in Paris in their apartment on rue Monsieur-le-Prince: Jacques was working out of an office in the Ministry of War, Odette was spending time again at the Musée Guimet, their maid had returned to the household, and the twins were enrolled in school. There was a lot of talk around the house about politics and the military. When one or the other boy did something good, one brother would “promote” the other to “lieutenant” or “colonel,” and he would be allowed to wear their father’s FFI armband.

The happy reunion was to be short-lived. The war was not over. As Camus had written earlier in Combat: “We have enjoyed our victory but have yet to see the victory of all. And we now know that all we have won is the right to go on fighting.” Hitler and Germany appeared determined “to end it all in the most tragic and theatrical of suicides” and to “impose a heavy price in blood.” Thus, Camus cautioned his fellow Frenchmen, “We must convince ourselves that the war is going to last and accept the sacrifices of victory as courageously as we assumed the burdens of defeat.”

If France was to regain her honor, and to earn a place at the victors’ table, the French and their army needed to fight, and to fight well, to the end of the war. De Gaulle told Leclerc in early October 1944: “It is essential that we participate in the future battles of 1945 with maximum force. Nothing is more important for the moment than to form new large units.” By that time, the combined British, Canadian, and American forces had well over two million men and counting in the European theater, whereas the entire French Army constituted just 250,000 troops that had been drawn from throughout her empire. The largest source of fresh French manpower and fighting spirit was the FFI, which comprised about 200,000 men. The FFI was far from a professional army, however. Many of its members were under twenty years old and had therefore not received any conventional training. Large bands of maquis had fought the Germans and liberated some areas on their own, but advancing into well-defended Germany as the armies now had to do—that was an altogether different proposition and would require close coordination among Allied forces. The immediate challenge to the French command was to integrate the untrained, poorly equipped, largely undisciplined, and politically fractious FFI into the French Army. That would be a complex task that required people with excellent knowledge of the Resistance and the FFI, who had the trust of Communist groups, and who could work within the hierarchy and discipline of the French Army.

It was a job for someone like Jacques Monod.

He was reassigned from the FFI to the French 1st Army (La première armée française) and received his orders in November 1944: “To assist … in the study and the development of plans concerning the integration of the French Forces of the Interior in the First Army.” Monod was to serve in the cabinet of Gen. Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, the charismatic head of the 1st Army and a future marshal of France. Wounded four times in World War I, de Lattre became the youngest French general in 1939, and his 14th Infantry Division performed well during the invasion of 1940. He then commanded French Army Group B, the predecessor to the 1st Army, in the Allied landings in southern France in mid-August 1944 (Operation Dragoon). He took Toulon and Marseille, then fought his way north, pushing the Germans back into the Vosges Mountains.

Passionately devoted to France, de Lattre was an inspiring leader, but also very demanding of his soldiers and staff, and often a stickler for discipline. Nevertheless, he was enthusiastic about incorporating the Resistance into the regular Army—in spite of the skepticism of both parties—and was determined to “win over this vibrant and tumultuous force without distorting it.” The effort was to become known as the “Amalgamation.”

One major challenge was the shortage of equipment—the FFI needed uniforms and weapons, and it had to rely mostly on captured German arms. A second, more difficult, challenge was the great difference in cultures within the regular Army and the maquis. The general strategy was to pair FFI groups with regular units. De Lattre likened the process to a chemist mixing test tubes of chemicals: some reactions went smoothly; others did not and had to be remixed. Moreover, these experiments had to be conducted in the midst of the battle, as most FFI units to be organized and trained were already in the front lines. Monod oversaw several such experiments and spent much of the brutal winter traveling on icy roads to and from the front lines in a jeep, visiting units, managing problems, and consulting with de Lattre as the 1st Army battled its way to and across the Rhine.

De Lattre could be personable, thoughtful, and charming. He was very appreciative of, and even affectionate toward, Monod, calling him his “most precious auxiliaire.” By February, an impressive 137,000 FFI had been integrated into the 1st Army that invaded southern Germany; took Karlsruhe, Stuttgart, and Ulm; crossed the Danube; and entered Austria in late April 1945.

By the first of May 1945, Monod believed that the Germans were finished. He wrote to Odette:

My dear Odette,

I am thinking about you, you before anything else this morning, as I just heard that probably today or tomorrow will be the last day of the war. I am thinking about you, about our little ones, about us, about our life about to resume its course, about our happiness …

There is a big piece of work to be done in the next couple of weeks, because everything has to be settled between the 15th and the 20th. But I will have at least the satisfaction that I would leave only when the situation would be stabilized, and after I would have reached my goals for the most part, and I am sure by now to be able to ask for demobilization the 31st without remorse.

I just heard the radio again: the English will be in Lubeck tonight or tomorrow probably. How wonderful to see Étienne [Odette’s

brother, a POW] again. If I could go get him!

My darling, I hold you in my arms. If only we could have been together today.

I adore you.

On May 8, de Lattre flew to Berlin and signed the Germans’ instrument of surrender on behalf of France. The war was officially over.

Parisians again poured into the streets to celebrate. Camus summoned his prose once again to mark the day of Victory in Europe. He cast French joy in the broader terms of the universal quest for freedom and his concept of rebellion:

History is full of military victories, yet never before has a victory been hailed by so many overwhelmed people, perhaps because never before has a war posed such a threat to what is essential in man, his rebelliousness and his freedom. Yesterday belonged to everyone, because it was a day of freedom, and freedom belongs either to everyone or to no one …

This war was fought to the end so that man could hold on to the right to be what he wants to be and to say what he wants to say. Our generation understood this. We will never again cede this ground.

Camus also acknowledged the losses that virtually everyone had suffered. But as someone who did not believe in eternity, he could not offer that solace. Rather, as one who saw life as a revolt against death, and who advocated living life to the fullest, Camus had wrestled with how to justify the conscious risk and sacrifice of Resistance members. Could he honestly justify their cause as one worth dying for?

In an earlier editorial, Camus had drawn a contrast between the sacrifice made by religious believers, who saw life as a “way station” and who could hope for martyrdom, and nonbelieving Resistance members: “Many of our comrades who are no longer with us went to their death without hope or consolation. Their conviction was that they were dying, utterly, and that their sacrifice would end everything. They were nonetheless willing to make that sacrifice.” That willingness Camus defined and praised as “lucid courage.” In his V-E Day editorial, he located the meaning of their courage and sacrifice in the greater good of mankind’s lasting freedom: “Those of us who are still waiting or still weeping for a loved one can enjoy this victory only if it justifies the cause for which the missing and the dead suffered. Let us keep them near us and not consign them to the definitive solitude of having suffered in vain. Only then, on this overwhelming day, will we have done something for mankind.”

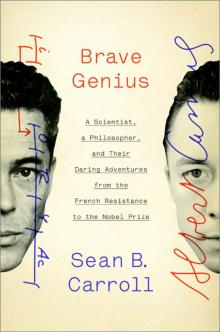

Brave Genius

Brave Genius