- Home

- Sean B. Carroll

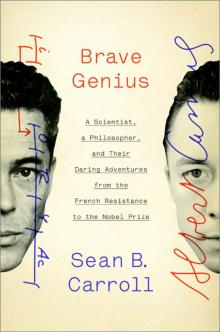

Brave Genius Page 21

Brave Genius Read online

Page 21

Often dining and drinking together, the three unconventional writers developed a sense of solidarity, and Camus was introduced to a wider circle of interesting artists. Camus was put in charge of a cast that included de Beauvoir and Sartre and that was invited to stage a public reading of a surrealist play that Picasso had written in the 1920s. Performed in a mutual friend’s living room, the standing-room-only audience for Le Désir attrapé par la queue (Desire caught by the tail) included Picasso himself, as well as the painter Georges Braque, and a variety of poets, directors, and actors. In appreciation for their efforts, Picasso invited the illustrious cast back to his apartment.

Camus, Sartre, and de Beauvoir in Picasso’s apartment. This photo was taken at a reunion of the cast and audience of the reading of Picasso’s play, staged in March 1944. Beauvoir is standing at the far right, Picasso is standing third from the right, Sartre is seated at the far left, Camus is to his right. (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

CAMUS WAS FOLLOWING his own prescription and living fully—working at Gallimard by day, seeing his friends in the evenings, working for Combat, and carving out a few hours for his own writing. He was working on the rewrite of his play Le Malentendu (The Misunderstanding), part of his cycle of the absurd, about a man who returns home from living overseas to discover his mother and sister have been taking in lodgers and killing them. He hoped to have it staged that summer.

Camus even found room for a new love. Among the audience the night of Picasso’s play reading was twenty-two-year-old Maria Casarès, who, despite her youth, was already a noted and experienced actress on the Paris stage. At the time, she thought Camus was a fine actor, but she could not have imagined that she would soon be tapped for the female lead in his new play. She met Camus at a work meeting in the director’s apartment and was immediately drawn to his “extraordinary presence” and his air of vulnerability. Camus was struck by Casarès’s dark beauty and her expressive eyes, and was deeply impressed by her talent. Her background was equally admirable. Born in Spain, she was the daughter of Santiago Casares y Quiroga, who served briefly as prime minister and minister of war of the Republic in 1936 until the Civil War broke out. Though just fourteen at the time, Maria volunteered as a nurse in Madrid hospitals, tending to the wounded. She and her mother and father then escaped to France just before the border was closed. After the Germans invaded France, Maria entered Le Conservatoire and began acting. Her acclaimed debut in the title role of Deirdre of the Sorrows in 1942 put an end to her formal studies as she became instantly in demand.

An intense and public affair started soon after she and Camus met. Francine was in Algeria, so Camus took Maria around Paris to his favorite cafés and restaurants. One reason why Camus was able to live such a public life while a member of Combat was that, unlike Monod’s scientific colleagues, none of his colleagues on the newspaper staff knew his true identity. He had no past associations with anyone (except Pia). “Bauchard” simply appeared at staff meetings and did his job. Camus also had protection beyond his pseudonym. The network had provided him with false papers in the name of “Albert Mathé,” a journalist who was born near Paris. Jacqueline Bernard was stunned when he eventually told her who he really was.

It was not the case that Camus and his comrades were in any less danger than other resistants. If anyone was followed to the concierge’s back room or caught with printing materials, everyone was exposed. Indeed, the Combat movement suffered many blows from the Gestapo during the winter and early spring of 1944, and some landed very close to Camus.

On January 28, the same day that Marcel Prenant was taken, Jean-Guy Bernard and his wife, Yvette Bauman, were expecting Jean-Guy’s sister, Jacqueline, for dinner at their apartment on the rue Boissy-d’Anglas. Jean-Guy was head of the N.A.P.-Railways, a branch of the Resistance in charge of infiltrating and interfering with rail transport. Yvette was in charge of social services for Combat and the MUR. Jean-Guy went to answer the door, expecting Jacqueline, but she happened to be running late. The door was pushed in by two Gestapo agents, who then took the couple away. Jacqueline had escaped arrest merely by chance. Yvette Bauman was subsequently deported to Ravensbrück; Jean-Guy died in transport to Auschwitz.

On March 8, the Gestapo caught up with Combat’s printer, André Bollier (Vélin), in Lyon. It was actually the second time he had been captured; he had promptly escaped from the French police two months earlier and gone completely underground. Although just twenty-three years old, Bollier was a vital part of the movement. He had devised the scheme in which the newspaper was printed not only at a plant in Lyon but at more than a dozen other presses around the country, which ensured its wide distribution. He also set up a phony company in order to import newsprint stock … from Germany. He did not shrink away from action, either. He had led a small armed band that broke Combat cofounder Berty Albrecht out of a psychiatric hospital in December 1942. After being tortured repeatedly and threatened with execution, Bollier escaped from a military hospital and resumed printing Combat.

In late March, the Gestapo struck again at the heart of the movement. Pierre de Bénouville had a network of people and a handful of apartments in Paris that handled daily courier messages, composed coded replies, typed them out, and shipped packets regularly to Switzerland. The Germans caught one of de Bénouville’s men in Annemasse with documents that compromised his typist. She managed to alert the network while the Gestapo searched her apartment, but not everyone was warned in time. Claude Bourdet, who had become head of Combat when Henri Frenay went overseas, and whom Camus had also met, rang at the typist’s apartment and was greeted by a revolver pointed at his face. The Germans found more addresses and began to set traps. Miranda was grabbed off the street on his way to a meeting. Alain de Camaret (“Nizan”), de Bénouville’s longtime friend and lieutenant who knew everyone in the organization, was snatched at another apartment. The Gestapo almost nabbed de Bénouville as well. He and his wife packed their bags in a hurry and left their apartment just in time. They took refuge with a friend in Paris who was not in the Resistance and would not be in any address book the Germans might find.

THE GERMANS’ AND Joseph Darnand’s aims were to crush the Resistance. Yet, despite the loss of so many commanders as well as foot soldiers, movements carried on. The Comet Line was rebuilt several times, de Bénouville rebuilt his network, and Combat continued to publish. Indeed, in March 1944, Camus authored his first (anonymous) editorial for the newspaper, in which he urged readers, particularly those who had been bystanders up to that point, to join the Resistance and to battle the Germans. Under the headline “Against Total War, Total Resistance,” Camus wrote: “You cannot say, ‘This doesn’t concern me.’ Because it does concern you. The truth is that Germany has today not only unleashed an offensive against the best and proudest of our compatriots, but it is also continuing its total war against all of France, which is exposed in its totality to Germany’s blows.”

Recounting recent episodes of German reprisals, Camus continued:

Camus’s false identity card, in the name of Albert Mathé, writer. All of the information on the card—birth date, place, parents—is false. (Courtesy of Collection Catherine et Jean Camus, Fonds Camus, Bibliothèque Méjanes, Aix-en-Provence, France. All rights reserved.)

These dead Frenchmen were people who might have said, “This doesn’t concern me.” …

Don’t say, “I sympathize, that’s quite enough, and the rest is of no concern of mine.” Because you will be killed, deported, or tortured as a sympathizer just as easily as if you were a militant. Act: your risk will be no greater, and you will at least share in the peace at heart that the best of us take with them to the prisons …

Total war has been unleashed, and it calls for total resistance. You must resist because it does concern you, and there is only one France, not two. And the incidents of sabotage, the strikes, the demonstrations that have been organized throughout France are the only ways of responding to this war. That is what we exp

ect from you.

CHAPTER 14

PREPARATIONS

If they attack in the west, that attack will decide the war. If this attack is parried, then the whole story is over.

—ADOLF HITLER, December 20, 1943

NO MATTER HOW MANY MIGHT JOIN THE EFFORT, THE RESISTANCE could not hope to dislodge the Germans on its own. The French were vastly outgunned and outnumbered. In the spring of 1944, the Germans had fifty-eight divisions in France comprising some 750,000 soldiers, whereas of the roughly 40,000 resistants in the greater Paris region, fewer than 1,000 were armed. The ultimate military value of the sorts of actions that Camus urged, as well as the intelligence being fed to Switzerland and London, was to help prepare the way for an Allied landing by damaging German capabilities. The sabotage of railroad, telephone, and electricity lines was intended to hamper German war production, the movement of supplies, and the mobility of troops, while intelligence gathered on the locations of fighting units, supply and munitions depots, and key factories within France was used to guide the Allied bombing effort.

The impact of sabotage carried out by the Resistance was substantial, especially on the railroads. One argument that Resistance leaders had been repeating to Allied commanders was that their small action teams were, in certain circumstances, much more precise and effective at destruction than high-altitude bombing. For example, it was much easier for a few men or women who knew the local landscape and railroad timetables to sever a rail line, derail a train, or blow up a locomotive than for a bomber to hit such small targets from 20,000 feet. Moreover, such acts of sabotage avoided the collateral damage of bombing raids on civilian lives or property, as well as avoided risking aviators’ lives. Statistics supported those claims. From January to March 1944, the Resistance destroyed more than 800 locomotives, compared to 387 hit by the Allied air campaign. Altogether, from June 1943 to May 1944, the Resistance destroyed 1,822 locomotives and 2,500 freight cars and damaged at least 8,000 more.

The cutting of rail lines was also widespread, as small amounts of well-placed explosives were sufficient to destroy short sections of track. In October and November 1943, Vichy police reported more than 3,000 attempted attacks on the rail system, with more than 400 successful acts in November causing major damage, including more than 130 derailments. Individual lines were hit repeatedly, as soon as possible after repairs to prior damage had been made. For example, the Paris–Brest rail line, which carried supplies for the fortification of the German defenses along the so-called Atlantic Wall, was cut twenty-four separate times by saboteurs from January to May 9, 1944.

No one in the Resistance knew how long such efforts would need to be sustained, however, because no one in France knew the time or the place of the planned Allied landings. Not even de Gaulle in Algiers or General Koenig in London was told of the plans or the date. With arrests of Resistance leaders so frequent, Allied planners deemed it too dangerous to disclose any specific information. Instead, the FFI and other, unaffiliated groups were told to listen to the BBC on the first, second, fifteenth, and sixteenth of each month for prearranged coded messages that would alert them that invasion was imminent. They were then to listen for subsequent confirmatory messages that would indicate that the landings would be taking place within forty-eight hours. The latter would also be the signals to each region or group to begin previously planned operations against rail, road, and communications targets, dubbed Plan Vert (green), Plan Tortue (tortoise), and Plan Violet (purple), respectively.

Monod and other operations men thus had the dual tasks of planning and carrying out actions for some indefinite period prior to the landings while also developing plans for the crucial hours, days, and weeks after the invasion. As months passed without the Allies landing and without any signal from the BBC that the event was imminent, and as arrests of leaders and comrades mounted, the daily tension and anxiety of Resistance work took a toll. It was difficult not to feel discouraged at times. One evening in April, Monod and Noufflard returned to her home to finish some work, exhausted again from an already long day. Suddenly, sirens went off and they heard explosions in the distance. They hurried up to the roof of the building and looked east over the city. They were transfixed by the bright flashes of one explosion after another lighting up the night sky. A continuous roll of thunder shook the building, amplified by the roar of plane engines and the crackling of antiaircraft fire. It was a massive raid on marshaling yards just outside the city. “Here they come!” Noufflard thought, hoping that such large-scale and systematic destruction, so close to the city, meant that the invasion might not be too far off.

Marshaling yards that fed as many as ten or twelve rail lines and covered many acres were key targets that were best attacked by heavy bombers. The combined effect of Resistance saboteurs and Allied bombers was to reduce rail traffic dramatically across France in the first half of 1944. The primary military effects of that reduction were to curtail the flow of supplies such as concrete and steel for the construction of German defenses along the west coast, and to force the diversion of thousands of defense construction personnel to repairing the railroads.

FOR THERE HOURS THEY SHOT FRENCHMEN

Tracks were repaired, and destroyed equipment was replaced. The Resistance was thus engaged in a continuous race with the Germans, forcing them to make repairs and to supply replacements, while hoping to escape reprisals. But the reprisals grew increasingly brutal. On April 1 and 2, 1944, a horrific episode unfolded in Ascq, a small village in the Pas de Calais region of northern France near Lille. A train carrying soldiers of the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend (“Hitler Youth”) from Belgium toward Normandy was blown partly off the tracks as it approached the station at Ascq just before eleven p.m. Two cars were derailed, but no one on the train was injured. Nonetheless, the troops were now vulnerable to Allied air attack, and enraged.

All German units in the west had been issued new orders in February concerning how to respond to such “terrorist” acts: they were to seize civilians in the immediate area and to burn down any houses from which they took incoming fire. The commanding officer of the Hitlerjugend convoy took matters further, as Camus recounted in his second anonymous editorial in Combat, entitled “For Three Hours They Shot Frenchmen”:

At around 11 that night, M. Carré, the station chief at Ascq, having been awakened at his home by night shift personnel, was on the telephone dealing with the situation when a German transportation officer entered his office screaming, followed by a number of soldiers who used their rifle butts to beat M. Carré along with M. Peloquin, a senior clerk, and M. Denache, a telegrapher, who also happened to be on the premises at the time. The soldiers then withdrew to the office doorway and from there fired on the three prostrate employees with submachine guns … Then the officer led a large contingent of troops into the town, broke down the doors of the houses, searched them, and rounded up some sixty men, who were marched to a pasture opposite the station. There they were shot. Twenty-six other men were also shot in their homes or thereabouts …

The executions did not stop until officers of the general staff arrived on the scene. The killing went on for more than three hours.

Whether it is possible to conjure up vividly enough an image of a scene described in such blunt language I do not know.

Camus declared that the massacre of eighty-six men at Ascq showed how the enemy “is increasing his efforts, outdoing himself, each time descending a little deeper into infamy and a little further into crisis … beyond what anyone could have imagined.” He closed his editorial by expressing the hope that “the image of this little village soaked in blood and from this day forth populated solely by widows and orphans should suffice to assure us that someone will pay for his crime, because the decision is now in the hands of all the French, and in the face of this new massacre we are discovering the solidarity of martyrdom and the power that grows out of vengeance.”

While Camus intended for his descriptions of German reprisals to arous

e further support for the Resistance, such incidents often had the opposite effect. The Resistance was resented by many in the general population and blamed for the increased repression by the Germans and the Milice, and the grief that brought. The German policy of reprisals was in fact intended to provoke anti-Resistance sentiment, and it worked to a significant degree.

Nor, despite four years of occupation, was the general population necessarily looking forward to an Allied invasion that could bring widespread destruction. The Allied bombing campaign was a potential preview of what was to come. The air campaign against urban targets such as marshaling yards was escalated in April at the direction of Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe. Eisenhower and his planners saw the bombing campaign as critical to the success of the invasion, but they knew that there would be considerable civilian casualties. Attacks on installations at Le Havre and Lille in April left thousands homeless, heavy night raids on April 21 over the marshaling yard at Saint-Denis and the Gare de La Chapelle killed 640 Parisians, and 400 civilians were killed three days later in a daylight raid on the marshaling yard at Rouen.

Both the Germans and Vichy sought to exploit such incidents and to raise doubts about the success of an invasion in their propaganda. After bombs fell on Paris, the collaborationist press labeled the Allied airmen les gangsters de l’air and declared: “Montmartre and the northern suburb of Paris have suffered from the most violent Anglo-American terrorist bombardment since 1940.” On April 26, 1944, Marshal Pétain made his first and only wartime visit to Paris, ostensibly to attend a service at Notre-Dame for the victims of the recent bombardments. Despite all that had transpired in the preceding four years, he was cheered by large, enthusiastic crowds along his route, and spoke to more than ten thousand people gathered before the Hôtel de Ville. Two days later, he addressed the entire nation by radio. Under some pressure from the Germans, he condemned the Resistance and identified Bolshevism as France’s principal enemy:

Brave Genius

Brave Genius