- Home

- Sean B. Carroll

Brave Genius Page 20

Brave Genius Read online

Page 20

THE NOUFFLARDS WOULD continue to shelter whoever was sent their way, including another American bomber’s navigator, but Geneviève was determined to join an organization and entrer dans le bain (get into the bath), in the slang of the Resistance. She told Monod that she was aware of the risks and had thought her decision through. She was, in fact, very nervous, as the prospect of being tortured terrified her. She explained to Monod that no one could know how one would react in that circumstance. She knew people who had been tortured and could not have predicted who would have buckled and who’d remain silent.

Monod told her, “Okay, all right, come tomorrow.”

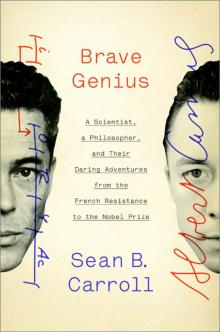

Geneviève Noufflard, from her wartime identity card. (Courtesy of Geneviève Noufflard)

GENEVIÈVE WAS PUT to work right away as a “liaison agent.” The Resistance could not use the telephone or the mail for fear of being intercepted, so people were used to transmit information. In order to exchange orders, letters, or documents, liaison agents met in the streets, or at cafés, or in churches, or in offices—anywhere where two people could have a casual encounter without attracting notice. Noufflard walked or rode a bicycle to each rendezvous. It was too dangerous to take the subway when carrying any document because the trains and stations were the frequent targets of police controls and searches.

To conceal whatever she was carrying, Noufflard hid items in her clothes, or in shopping bags under a load of vegetables, or under feminine articles that a potential searcher might be too embarrassed to handle. It was difficult to pass documents hand-to-hand in the street without being noticed, so papers were often disguised as mail, enclosed in envelopes with imaginary addresses and even stamps on them. These were best passed inside a post office, or by innocently asking the contact for the favor of mailing a letter. Monod showed Noufflard one of his favorite places for the safekeeping of sensitive papers: just outside the door of his lab at the Sorbonne there was a mounted giraffe whose hollow leg bones accommodated documents that the Gestapo would have loved to find.

The job required a great deal of discipline. Normally, everyone Noufflard was to meet had been personally introduced to her by an FTP member she had also met. If she was meeting someone she did not know, it was critical that she recognized the right person. That was done by giving some prearranged sign or code words. So, for example, when Geneviève was to meet someone whom she was told would be carrying a certain type of wine, she was to say to him: “Where is the Parc des Princes?” And the reply was to be: “You are there, mademoiselle.” For extra safety, they each also carried bus tickets with numbers on them.

The work entailed constant danger. It was most critical to make sure that she was not being followed, for if the Gestapo or the Milice tracked her, she would lead them to other agents and to their bosses, and all would be arrested. The Germans had agents in the streets, and knowing that everyone was compelled to work, they watched for revealing behavior. It was dangerous even to wait for someone on a sidewalk. She might be asked for papers and searched, or those watching might wait to see whom she was waiting for and follow them. The rule was not to wait much more than five minutes at a given rendezvous. There was usually a backup meeting, called a repêchage (literally, “re-fishing”), if one missed an appointment.

Next to the constant anxiety, the hardest strain was on her memory. Noufflard could not write down any details, and neither could she meet people at the same place twice, just in case either was observed the first time. So she had to memorize all of the times, places, people, and aliases to meet at her appointments, sometimes up to fifteen different meetings in the course of a day. Then she had to memorize a whole new set of instructions for the next day.

ARRESTS

Despite the emphasis on security in the FTP, there were lapses. Marcel Prenant, alias “Auguste,” was living a double life similar to Monod’s. Along with his role in the FTP, he had a laboratory at the Sorbonne, his Jewish wife and mother-in-law were living outside of Paris, and he was staying away from the family apartment on rue Toullier near the Sorbonne. He was living instead in Port Royal Square, with his friends and fellow resistants Vladimir and Joulia Kostitzine, the latter of whom worked in his lab. On the morning of January 28, 1944, he had a rendezvous on a quiet street in the Paris suburb of Gentilly with a delegate who went by the name of “Robin.” The FTP man was responsible for one of the most important regions of the country—the sector that included Normandy, one of the potential sites of the hoped-for Allied landing. Prenant saw Robin each week, and during the interval Robin would visit his sector. In this particular encounter, Prenant was planning to reproach Robin, as he had learned that the delegate was marking his meetings down in a notebook.

Prenant entered the empty street but saw no sign of Robin. Unconcerned, he kept walking until he saw four men come out from behind some doors, pistols drawn. One of them said, “German police.” Prenant knew it was hopeless. They handcuffed him and put him in a waiting car. Inside, he saw Robin, collapsed in the corner, having clearly been beaten. Prenant knew instantly that he was a victim of Robin’s notebook. They were driven along the Left Bank of the Seine until they reached the rue des Saussaies, headquarters of the Gestapo in Paris.

Prenant was pretty sure what would come next. He was seated in front of an officer, behind whom he could see a collection of truncheons of various types. Leaning back against the display, standing mute, arms crossed, were three scar-faced brutes with their eyes riveted upon him. Prenant had thought many times about the attitude he would take if he fell into the hands of the Gestapo. He knew that he was done for; his single concern was not to give up any information that could be used to grab any of his comrades or used against the FTP in general. Prenant had no compromising documents on him. But his lab was a different matter, and he was sure that it was already being searched. One consolation of that fact was that the search would alert his friends that he had been arrested.

The interrogation began. The officer asked what each of the keys on his keychain were for, what the abbreviations meant on the papers he had in his pockets, and what his role was in the Resistance. The trick was to give away small things, either facts that the Gestapo knew already or that would at least give the appearance of being truthful. Prenant answered each question, including admitting that he was part of the FTP. After a brief lunch break, the officer informed Prenant that they had searched his lab and his home, where they arrested his son. “But you don’t live at your home?” the officer asked.

“No,” Prenant replied.

“Then where do you live?” his interrogator asked.

“I will not tell you,” Prenant said. He did not want to say where he was living, or at least he wanted to hold out until his roommates had sufficient time to get away.

“We shall see about that,” the Gestapo man said.

The officer was determined to find out who and where Prenant’s associates were. After trying to coax the address out of Prenant, he said, “That’s enough! Either you give me this address immediately, or I will put you in the tub. Do you know what that is?”

Prenant had heard of la baignoire as a method of torture in which one’s head was held underwater until just before drowning. The officer gave him another chance; Prenant refused. He and his henchmen then took Prenant upstairs to the fourth floor of the building and into a small bathroom. After asking for the address one last time, which Prenant refused again, the men seated him on the rim of the tub and tossed him in. One of the men then grabbed Prenant’s ankle chain and yanked it up high, plunging his head under the very cold water. They let him up after a short time, then submerged him again for much longer. Prenant deliberately thrashed about, splashing his torturers. They let him up again, then plunged him down again, and continued to repeat the process. After the eighth cycle, Prenant decided that he was risking an escalation of the torture and that he had bought enough time for his friends to escape. When the officer asked if he was ready to answer, he said “Yes,” and gave the Port Royal Square address. Wh

ile Prenant was allowed to dry off, the other men ran off to his hideout. They found it empty and did not find any incriminating papers in Prenant’s room. The Kostitzines had taken documents out of his briefcase and torn them into little pieces before flushing them down the toilet and making their getaway. After a brief interrogation the next day, Prenant was transferred to Fresnes Prison; he was eventually sent to Neuengamme concentration camp.

MALIVERT

The loss of Prenant was a blow to the FTP, and while the leadership had confidence in Prenant’s ability to defy his interrogators, no one could be certain whether the damage would be limited to Prenant and Robin. The arrests ratcheted up the anxiety and tension throughout the organization, but just like other Resistance groups that had suffered arrests, the movement had to continue and the lost leaders had to be replaced. The FTP promoted Georges Teissier, Monod’s brother-in-law, to take Prenant’s place as chief of staff. At the same time Monod was given a new role as FTP’s delegate to a new organization, the French Forces of the Interior (Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur; FFI), which united the various Resistance military groups: the Secret Army (itself a combined force of Combat, Libération-Sud, and Franc-Tireur); the ORA (L’Organisation de Résistance de l’Armée); and the FTP. Created in large part in anticipation of the battle for liberation, the FFI was designed to coordinate Resistance activities both before and after the Allied landing. Gen. Marie-Pierre Koenig of de Gaulle’s staff in London was its overall head, and Pierre Dejussieu (“Pontcarral”) was appointed its chief within France.

There was a commandant in charge of each of roughly twenty regions of France. And in each region, there were officers in charge of different military departments such as intelligence (Deuxième Bureau; G2) and operations (Troisième Bureau; G3). Monod was made head of operations for the Paris region. The Deuxième Bureau’s agents were to collect information on potential targets. These would be passed to Geneviève Noufflard, who would then bring them to Monod, who was in turn responsible for selecting which actions would be taken and for giving orders to action teams.

Monod discovered that he could not maintain his double life for long. Along with his new responsibilities, and on the heels of Prenant’s arrest, came news of the arrest of another colleague from the Réseau Vélites, Raymond Croland, who knew Monod’s identity and activities. The cofounder of the network and a member of the same department as Georges Teissier at the École Normale Supérieure, Croland was carrying out experiments throughout the war on the induction of mutations in bacteria and fruit flies by X-rays. Late in the afternoon of February 14, while Croland was waiting for a contact from London in the office of his fourth-floor biology laboratory, five French and German policemen in plainclothes arrived at his building, blocked off the entrances and exits, and arrested him.

The establishment of the FFI also increased Monod’s exposure because, as it was another new Resistance superorganization, the FFI and those within it instantly became priority targets for the Gestapo. Monod decided that he had to plunge fully into clandestine life (l’illégalité)—sleeping at different addresses and staying away from the apartment on rue Monsieur-le-Prince. He also changed his alias. The creation of the FFI would not instantly solve long-standing problems such as the shortage of weapons. Monod was skeptical that he or his bureau would have the means to make an impact on the enemy. So he chose an ironic pseudonym, named after a character in Stendhal’s novel Armance who was impotent: “Malivert.”

He kept working on the weapons problem. He made another trip to Switzerland, but this time it was in midwinter and, worse, the area around Annemasse (the usual crossing point) was swarming with Darnand’s militiamen. Monod, de Bénouville, and “Miranda,” the defense chief of the maquis, took an alternate route on foot through the snowy Jura Mountains. De Bénouville was very impressed with and appreciative of Monod’s calm demeanor; with the collar of his Canadian jacket turned up against the wind and cold, Monod looked “as calm as though he were on his way to the subway.” On their way back, the men found bicycles in the town of Morvillars and pedaled to Belfort, which was full of German soldiers. They reached their train, blended in with the other passengers, and made it back to Paris again safely.

Such adventures and the requirements of a clandestine lifestyle were not compatible with continuing work in the lab, even if Monod was hiding out in the attic of the Pasteur. Just as he had in the winter of 1940, Monod had to step away again from his research. The timing was unfortunate, for, despite all of the distractions, he had been making important progress. During the winter of 1943–44, he had begun a new set of experiments with Alice Audureau, a graduate student in Lwoff’s laboratory at the Pasteur. Probing further into the phenomenon of double growth that he had rediscovered in his thesis, Monod and Audureau followed up on reports that strains of the E. coli bacterium that did not metabolize lactose could be coaxed into doing so by being grown on media containing lactose. There was a conflict in the literature as to whether this was due to an effect on an enzyme that was promoted by the presence of the sugar, as most thought, or due to a rare mutation. Audureau and Monod found that such strains were indeed mutants, which showed that the ability to metabolize lactose was a genetically determined characteristic of the bacteria, not a property promoted by the sugar. Moreover, such mutants were not rare. In fact, Audureau isolated several from a stool sample taken from her boss, Lwoff, which she and Monod mischievously dubbed E. coli ML, which stood for mutabile in Lwoffi or for merdae Lwoffi, depending on the audience. Genetics, and especially bacterial genetics, was in its infancy at the time, so the use of genetic investigations to clarify a physiological puzzle like enzyme adaptation was novel and powerful.

Monod managed to squeeze in a few more days in the lab before his Resistance work overtook him completely.

As his clandestine activities accelerated, he only dropped into the lab for odd supplies, like rubber stoppers. Monod needed them as silencers—not for weapons, but for a duplicating machine. He and Geneviève Noufflard sometimes had to make thousands of copies of bulletins or other documents. It was very difficult to do so without attracting attention.

Noufflard’s building also housed offices of the Department of Agriculture, and she learned that they had a splendid duplicating machine. To use it, they had to sneak in at night during the curfew hours and carry out the job without being seen or heard. Her concierge was in on the scheme and agreed to be the lookout.

She and Monod found that they had to move the machine into the corridor so that they could not be seen from the street. But there were people living on the floors below, and both the moving and operation of the machine made a lot of noise. If Monod and Noufflard were caught red-handed printing communiqués on the latest FTP activities, they would each be in dire straits. So Monod plucked two large rubber stoppers from flasks in the lab, cut them into four pieces, and made “shoes” for each of the four feet of the machine. At midnight, he and Noufflard took their own shoes off and, carrying ink, stencils, and two suitcases full of paper, crept into the offices, moved the machine, and made their copies. Finishing at dawn, they moved the machine back, packed up their copies and spent supplies, and lugged them out. The policeman on the street only saw a very affectionate couple who appeared to be heading off on a trip.

COMBAT

Camus was able to maintain a double life as a staff member of Combat and as a writer on the Paris scene. With so many friends in the Resistance, he found a variety of ways to contribute. Soon after he settled into a room at the Hôtel Mercure, just two hundred yards or so away from the Hôtel Lutétia, home of the German Wehrmacht, he sent a note alerting the Fayols that he was sending to them one of his friends from Oran who had also been trapped in France. This particular friend was Jewish, so Camus indicated that she “has delicate health from a hereditary infection.” His new job on the reading committee at Gallimard gave him an office in which to work on his own articles and to hide documents for others. It also put him into contact with a

number of other Gallimard writers, some of whom, like André Malraux, were wanted men. One day, Camus asked quietly around the office for help in lodging a “very important person.” Waiting outside on the street was Malraux, who was escorting the VIP—Capt. George Hiller, a British officer with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) who was arranging parachute drops to the Resistance. An editor took in Hiller.

In the course of his first few months back in the capital, Camus actually became more visible as he wrote for the stage and socialized with other writers and artists. He had met Jean-Paul Sartre when he attended the latter’s play Les Mouches (The Flies) on one of his journeys into Paris while staying at Le Panelier. As he settled into his new job, he began meeting regularly with Sartre and his companion Simone de Beauvoir in the cafés near Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Both the short, walleyed existentialist and the pioneering feminist were charmed by Camus’s good humor and enthusiasm, and impressed by his talents and intelligence. In talking about the war, politics, and the theater, Camus discovered that he had much in common with the couple, despite his much more humble upbringing.

The Café de Flore was a favorite haunt for the trio. Besides its clientele and its convenient location in the heart of the Left Bank, just a few blocks from the Gallimard Building, the Flore had the added appeal in coal-limited Paris of a wood-burning stove. It was there at their first meeting together that Sartre proposed that Camus direct his new play Huis Clos (No Exit) and perform the male lead. Camus accepted, and they began to rehearse in de Beauvoir’s room at the Hôtel la Louisiane. However, the venture was abandoned when the female lead, for whom the play had been commissioned by her husband, was arrested because of her contacts with the Resistance.

Brave Genius

Brave Genius