- Home

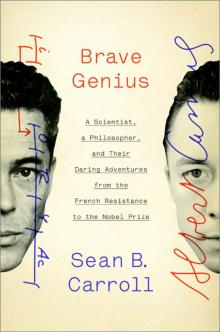

- Sean B. Carroll

Brave Genius Page 25

Brave Genius Read online

Page 25

Some of the trucks sweeping through the streets were leaving the city, part of a “strategic withdrawal” of some units; others were racing to the scenes of the major fight that had broken out at the Prefecture of Police, as well as skirmishes on the boulevard Saint-Germain, the boulevard and Place Saint-Michel, at the Place de l’Odéon, on rue Saint-Jacques, at the Palais de Luxembourg, and at Luxembourg Gardens.

EARLY THAT AFTERNOON, Camus and two friends braved the firing nearby and set out from the neighborhood of Les Invalides to make their way across the Seine. Prompted by news of the Allied advance, Camus had only recently bicycled back to Paris after several weeks of lying low in Verdelot following Jacqueline Bernard’s arrest. His purpose that day was a reunion of what remained of the Combat staff at 100 rue Réaumur, not far from where he and Casarès had had their encounter with the police. Pascal Pia was already there waiting for everyone. Marcel Gimont was also expected, along with Henry Cauquelin, an old friend of Pia and Camus from the days of Paris-Soir.

Once home to the newspaper L’Intransigeant, the building had for the past four years housed Paris Zeitung, the newspaper of the German occupation forces. A plan for the elimination of all German and collaborationist presses had long been decided. The provisionary French government in Algiers had issued a circular in May to ensure the resumption of news services upon liberation. All fifty-six dailies that had continued to be published in the occupied zone fifteen days after the armistice of June 1940, or the fifty-one dailies that continued to be published in the southern zone after November 1942, were to be suspended. In their stead would be the Resistance newspapers or those, like the Communist L’Humanité, whose publication had been banned by the Germans or Vichy. The rue Réaumur offices had been abandoned only days earlier. Now Combat was assigned three offices and a large room upstairs, above those of Défense de la France and Franc-Tireur. The place was a bit dingy, but the new tenants discovered a huge stock of canned food, reams of printing paper, and a case of grenades. Little forethought had been given to the security of the building, so the three newspapers’ staffs decided to put some of the grenades on a few windowsills and on the roof, just in case they might be needed.

Their authorization to begin publishing was to come from Alexandre Parodi, alias “Quartus,” the delegate-general of the Gouvernement provisoire de la République française (GPRF), the provisional government headed by de Gaulle. The GPRF had been created at the time of the landings in anticipation of the liberation of France. Parodi’s main tasks were to reestablish the government ministries and to serve as an intermediary between the GPRF and Resistance organizations. As fighting broke out, he was weighing many conflicting concerns: the determination of de Gaulle to establish his authority in France; the independent-minded Communists who held many positions in the FFI and who were determined to liberate Paris without outside help; the desire to preserve Paris as intact as possible and with minimal loss of life; and the uncertainty of the German’s military plans and their reactions to the escalating violence. Uneasy about the response the newspapers might provoke, Parodi was holding them back for the moment. In the meantime, each staff was preparing its first issues. With tanks rolling by on the street and reports pouring in from around the city, no one was leaving the building. Camus and the other staff members each found a corner in which to sleep.

THE POLICE AND the FFI at the Prefecture barely held out. The Germans attacked the building with tanks and inflicted heavy casualties. Outgunned and very low on ammunition, the men in the Prefecture appealed to the Swedish general consul Raoul Nordling to intervene. Nordling went to see Gen. Dietrich von Choltitz, who had just replaced Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel as commander of German forces in Paris on August 9. A veteran of both fronts, von Choltitz had earned the reputation of a committed Nazi officer, and Hitler wanted a firm hand in control of the 17,000-man Paris garrison. His direct orders from the Führer were to “stamp out without pity” any uprising in the city or any other acts of sabotage. To von Choltitz’s surprise, Nordling proposed a temporary cease-fire to allow for removal of the dead and wounded. Seeing the potential of returning the city to calm and avoiding further escalation of the battle, von Choltitz agreed. Nonetheless, it had been a costly day for both sides, with about 150 resistants and 50 Germans killed in the uprising.

JUST BEFORE DARK, Monod and Noufflard retreated to the roof of her house to survey the city. They sat in silence while listening to sporadic gunfire and the rumble of German tanks and vehicles moving in the direction of the Seine. It had been an intense day—a mixture of excitement, terror, rumors, anxiety, and hope—the first of who knew how many days of the battle for Paris.

TO THE BARRICADES!

Early the next morning, the Hôtel de Ville, the seat of political power in Paris, was occupied without a fight in the name of the provisional government. The occupation of buildings, however, worried Monod. He was concerned that the FFI could not hold buildings against the Germans’ superior firepower, as the battle at the Prefecture would have shown were it not saved by the cease-fire. Instead, he had an alternate strategy for the insurrection in Paris, one as old as the revolutions of 1830, 1848, and 1870. That same morning—Sunday, August 20—he dictated an order to Rol:

The development of operations in Paris demonstrates once more the grave error of occupying buildings or strong points, so well guarded as they are. In the large population centers, as much and perhaps even more so than in the countryside, the FFI can only have one tactic, that of the mobile guerrilla.

Concerning the actual situation in Paris, the possession of the Cité is an accepted fact of which the moral if not the strategic value is considerable, there should be no question naturally of abandoning this position, which ought to be held at any cost. But the command must look to create strong diversions everywhere and as often as possible. Consequently:

1) Multiply the armed patrols by car over the entire length of Paris and the outskirts.

2) Build, wherever possible, beginning with the large main streets frequented by enemy patrols, barricades that are powerful enough to stop automobiles, trucks, and scout cars with machine guns. These barricades should be built with twists and turns that allow the passage of friendly patrols.

3) They should be defended by armed groups that will have the mission of preventing enemy vehicles from penetrating the barricades.

4) The unarmed Milice Patriotiques and the population should be encouraged by means of posters and loudspeakers mounted on cars to participate in the construction of the barricades.

5) Alarm systems should be organized between the different groups defending successive barricades, in order to announce the arrival of tanks that the enemy will doubtless seek to use to force their passage. The barricade guards should then withdraw to the nearest buildings, and seek to attack the tank with grenades if they have them. If not, they should let them pass, and restore the barricade immediately thereafter.

… MALIVERT

Monod turned to Noufflard as she finished transcribing the order and said, with an impatient tone in his voice, “Of course, this order won’t be carried out. It is a shame, too; it might prove very successful.”

Monod was wrong on one count and right on the other. Rol did in fact promptly issue an order to build barricades, and the obstacles were very effective at hampering the Germans’ movements around the city. All across Paris, men, women, and children organized themselves into human chains: they dug up paving stones; hauled out furniture, mattresses, and kitchen stoves; rolled out old vehicles; cut off tree limbs or downed whole trees; gathered up sandbags; and stacked everything together into formidable barriers, some more than one story tall. Armed FFI, many of the men in open shirts, the women in shorts or summer dresses, and all wearing armbands with the FFI insignia, took up positions behind the barricades and in buildings overlooking the street, waiting to ambush vehicles that ran into their traps.

Noufflard did not stop to build barricades. She had other urgent duties, inc

luding delivering a message from Rol to Alexandre Parodi. The delegate-general was hoping to extend the cease-fire of the night before into a lasting truce with the Germans that would enable the handover of Paris to the French, while allowing the Germans to withdraw. Rol, who was not part of the discussions of the truce, objected, as did other Communists.

Noufflard bicycled over to deliver Rol’s message to Parodi at an apartment on avenue de Lowendal near the École Militaire. The delegate-general happened to be a very good friend of the Noufflard family. He was the brother of the magistrate René Parodi, who had stayed with the Noufflards for a time after the collapse in 1940 and died in Fresnes Prison in 1942. Living clandestinely in Paris for the past year, Alexandre had even shown up at Noufflard’s house once, sporting a new mustache. Parodi greeted Noufflard warmly and talked frankly with her about the situation in Paris.

After leaving Parodi, Noufflard had to navigate again the nearly deserted streets of the École Militaire district. She was very nervous, as the area had been reinforced by the Germans with their own barricades of barbed wire at the entrances and exits of all of their buildings. Machine guns also pointed down each street. Noufflard was relieved to get back home without incident.

Parodi was not so fortunate. After he and two aides were driven off toward another meeting, the car was stopped at a checkpoint. The men were found to be armed and carrying incriminating documents; they were arrested immediately. They identified themselves as “ministers of de Gaulle,” so the military tribunal to which they were taken contacted General von Choltitz for instructions. The troops had orders to shoot civilians carrying weapons. “Should we shoot them?” he was asked.

“Yes, of course. Shoot them!” von Choltitz said.

Before he hung up, he changed his mind. If the men were who they said they were, von Choltitz wanted to talk to them. Parodi and his aides were brought to von Choltitz’s headquarters at the Hôtel Meurice late that afternoon. De Gaulle’s representative and Hitler’s proxy met face-to-face, with Swedish consul Raoul Nordling trying to mediate. Nordling had told von Choltitz beforehand that if Parodi was imprisoned or shot, the Communists would take charge and chaos would ensue. The Kommandant told Parodi that the fighting must stop, and released him to Nordling’s custody.

But the fighting did not stop. Rol and his subordinates ignored the cease-fire and repeated the order to keep fighting. German vehicles were trapped and ambushed at the barricades, von Choltitz had more than 75 men killed, and French sacrifices also continued: 106 were killed and 357 wounded in the course of the day. The truce was defeated at a vote of the military action committee that evening.

IT WAS A momentous day for two particular Frenchmen. That morning, German troops removed Pétain from his headquarters at Vichy and moved him to the occupied city of Belfort on the German border. And on a fighter strip near Cherbourg, a twin-engine Lockheed Lodestar named France made an unscheduled landing. After four years in exile, de Gaulle had flown back to France from Gibraltar.

Upon arrival, de Gaulle was told, “There has been an uprising in Paris.” Visibly upset, he asked to see General Eisenhower in order to convince him to move on Paris. De Gaulle was promptly driven down to Eisenhower’s headquarters at Granville, on the coast near Avranches. As the two generals went over maps of the battle zones, de Gaulle warned Eisenhower that an insurrection could derail Allied war plans. Eisenhower was not at all convinced. He saw de Gaulle’s concerns as political, not military, and the Supreme Commander’s foremost concern remained routing the Germans. He did not want to risk getting entangled in Paris. De Gaulle came away empty-handed. Paris was on its own.

COMBAT CONTINUES

The next morning, Monod and Noufflard went to see Rol at his command post. They caught up with the FFI commander just as he was descending into his new secret subterranean headquarters far below the Place Denfert-Rochereau. Entering through a trapdoor in the basement of the headquarters of the Paris Water and Sewers Administration, Monod and Noufflard followed Rol, his secretaries, and a guard down 138 steps, into a labyrinth of dark stone and cement corridors lit only by Rol’s gas lamp. After passing by several signs marking the streets that ran above them, they reached a great metal door, which opened after a password was given. Once inside, Noufflard marveled at the clean, brightly lit offices that, despite their location deep within the Paris Catacombs, had fresh air. The offices were supplied with detailed maps of Paris and enough food for Rol’s entire staff. In addition to the city’s electrical supply, the command post also had diesel-powered and pedal-powered generators. There were public telephone lines, as well as a private network that went out to 250 points across Paris and its outskirts.

Part of the water and sewer works that dated back to the eighteenth century, the command post was organized by a Resistance engineer named Tavès who worked for the utility. It was connected to the more than three hundred miles of tunnels and catacombs running underneath the city so that one could cross between districts without going aboveground. Here, from this fortress eighty feet beneath Paris, protected from probing German eyes and ears, Rol intended to conduct the insurrection.

Jacques Monod’s identity card for the French Forces of the Interior (FFI), in his nom de guerre “Malivert.” (Courtesy of Olivier Monod)

Monod and Noufflard would each return to Rol’s lair in the coming days. To gain entrance, they would have to show their newly issued tricolor FFI identification cards. Thousands of cards would eventually be distributed; Monod was issued number 2 and Noufflard number 7.

FOR TWO DAYS, the Combat staff had been holed up in their much hotter, stuffier aboveground quarters preparing a first issue. Their electricity was unreliable, but the telephone lines around Paris were, fortunately, still working. The small team followed the rapidly evolving battles in the city, kept track of the Allies’ advance and the Germans’ retreat, and read the communiqués from the FFI, the Allies, and the provisional government. Of course, much news quickly became outdated, so dispatches had to be refreshed while they awaited final permission to publish.

Since their July meeting in his studio, Camus and his colleagues were determined that the editorial voice and identity of the newspaper was more important, at least to them, than the news they would publish. They had formulated a new motto to replace the original: “A Single Leader: De Gaulle; A Single Fight: Our Liberty.” The public incarnation of Combat would adopt “From Resistance to Revolution” as its creed. Camus had readied a long article bearing the same title and explaining their purpose, which was to look beyond the approaching liberation and to ask what kind of country they wanted to see emerge from “five years of humiliation and sacrifice.” Their answer was a France that honored what they saw as “a revolutionary spirit growing out of the resistance,” one that they would “define for the world and for ourselves, the image and example of a nation saved from its worst mistakes and emerging … with a youthful visage of grandeur regained.”

It was a markedly different tone, and a much more introspective and reflective path, than the one some of their competitors would take. While Combat spoke of honor, justice, and the work ahead, L’Humanité would declare “Death to the Boches and the Traitors!”

Finally, in the afternoon, under pressure from Pia and others, Parodi granted permission to publish. Operating with only intermittent supplies of electricity, the presses turned out 180,000 copies of Combat issue number 59—a single sheet printed on both sides. Street vendors hawked the newspaper for two francs.

One of the lead stories was an hour-by-hour digest of the insurrection, accompanied by a photo of a shirtless, armed FFI man, beret cocked on his head. It also reported that de Gaulle had arrived in France, and it announced that the newspaper would appear every morning. In the far-left column of the front page, Camus had composed a short editorial; it was signed only with an “x” as the liberation was not a fait accompli and the use of any names or aliases could be fatal. He entitled it “Combat Continues …”:

Toda

y, August 21, as this newspaper hits the streets, the liberation of Paris is nearing an end. After fifty months of occupation, of struggle and sacrifice, Paris is rediscovering the feeling of freedom, even as bursts of gunfire erupt at street corners around the city.

It would be dangerous, however, to return to the illusion that the freedom that is due of every individual comes without effort or corresponding pain. Freedom has to be earned and has to be won. It is by fighting the invader and the traitors that the Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur are restoring the Republic, which is the indispensable condition of our freedom …

The liberation of Paris is but one step in the liberation of France …

The combat continues.

“MOUVEMENT IMMEDIAT SUR PARIS!”

Indeed, the combat in the streets would continue. Late in the day on Monday, Parodi had made a second attempt to convince representatives of the various French factions to agree to a truce. He failed.

Tuesday, August 22, would see some of the heaviest fighting yet. At the intersection of boulevard Saint-Michel and boulevard Saint-Germain, the FFI destroyed several German trucks and took a dozen prisoners. But German tanks rolled through the main arteries, crashing through some barricades and attacking FFI positions. Three tanks attacked the central post office, four tanks attacked at the Panthéon, and several tanks fired on the Hôtel de Ville. The defenders’ main weapon against the machines were Molotov cocktails that were now being mass-produced daily by teams in several Paris university laboratories, using a recipe developed by Frédéric Joliot-Curie, the 1935 Nobel laureate in Chemistry. The mixture combined gasoline, sulfuric acid, and potassium chlorate, and ignited on impact. Indeed, Joliot-Curie’s lab at the Collège de France was one of the main manufacturing sites that were producing several hundred bottles a day.

Brave Genius

Brave Genius