- Home

- Sean B. Carroll

Brave Genius Page 13

Brave Genius Read online

Page 13

Well aware of the contradictory reports emanating from Radio London, Vichy and German sources tried to counter them. On August 17, two days after the costliest day for the Luftwaffe over Britain, Le Matin was compelled to run an editorial urging “that the French regain their common sense.” The article stated:

The war between Germany and England has entered a decisive phase and the result is not in doubt. However, some French seriously forecast England’s victory over Germany! Those French are certainly not asking themselves where are France’s interests …

It is England that led us to catastrophe. And one asks oneself how is it that there are still people in France who believe or who make believe that an English victory would be profitable for our country?

One despairs of French common sense.

“Common sense” was a common refrain, and also the suggested antidote to any sympathies expressed for de Gaulle. In the middle of the battle of Dakar, Le Matin decided that it must address those readers who had sent in letters declaring that the true French were those who had confidence in England, and who had written “Vive de Gaulle!”:

Thus, de Gaulle, traitor to his country, in the service of England, and condemned to death … still finds here defenders who have the audacity to write “Vive de Gaulle!”

One despairs over the common sense of certain of our compatriots.

Those French who understood English could also tune in to the BBC Home Service and sense Britain’s defiant, confident mood. A few days after witnessing the pivotal air battles over Britain from an RAF operations room, Churchill captured that mood when he addressed the House of Commons:

We have not only fortified our hearts but our Island … The people have a right to know that there are solid grounds for our confidence which we feel, and that we have good reason to believe ourselves capable, as I said in a very dark hour two months ago, of continuing the war “if necessary alone, if necessary for years”…

It is quite plain that Herr Hitler could not admit defeat in his air attack on Great Britain without sustaining most serious injury. If after all of his boastings and bloodcurdling threats and lurid accounts trumpeted around the world of the damage he has inflicted, of the vast number of our Air Force he has shot down, so he says, with so little loss to himself … if after all this his whole air onslaught were forced after a while to peter out, the Führer’s reputation for veracity of statement might be seriously impugned …

We believe that we shall be able to continue the air struggle indefinitely and as long as the enemy pleases …

The gratitude of every home in our Island, in our Empire, and indeed throughout the world, except in the abodes of the guilty, goes out to the British airmen who, undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning the tide of the World War by their prowess and by their devotion. Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.

The German losses were, in fact, unsustainable. Their attacks petered out by October 31, even if the exaggerated claims did not. Hitler quietly postponed, then abandoned, his plans for an invasion of Britain.

Churchill’s eloquent and passionate resolve was a far cry from what the French heard during the critical phase of the Battle of France, and directly opposed what they were hearing and reading from domestic sources. Despite Dunkirk, despite Mers-el-Kébir, and despite Dakar, the British were earning the admiration of the growing number of French who tuned to the BBC. And if there was any doubt about Churchill’s inclination toward France, he addressed the French directly, in good French, on Radio London on October 21. Delivered during an air raid on London, his opening lines set the tone of his fourteen-minute-long broadcast:

Français!

C’est moi, Churchill, qui vous parle. Pendant plus de trente ans, dans la paix comme dans la guerre, j’ai marché avec vous et je marche avec vous encore aujourd’hui, sur la vieille route. Cette nuit, je m’adresse à vous dans tous vos foyers, partout où le sort vous a conduit. Et je répète la prière qui entourait vos Louis d’or: «Dieu protège la France».

[Frenchmen! It is me, Churchill, who speaks to you. For more than thirty years, in peace and in war, I have marched with you and I am marching still along the same road. Tonight I speak to you at your firesides, wherever you may be, or whatever your fortunes are. I repeat the prayer around the louis d’or [a French gold coin]: “God protect France.”

Churchill then went on to warn the French of Hitler’s ultimate aims: “I tell you what you must truly believe when I say that this evil man, this monstrous abortion of hatred and defeat, is resolved on nothing less than the complete wiping out of the French nation … All Europe, if he has his way, will be reduced to one uniform Bocheland.”

He urged the French to “rearm your spirits before it is too late” and to “have hope and faith, for all will come right.” He then made a request: “What we ask of you at this moment in our struggle to win the victory which we will share with you, is that if you cannot help us, at least you will not hinder us. Presently you will be able to weight the arm that strikes for you, and you ought to do so.” He vowed to “never stop, never weary, and never give in” until “the task of cleansing Europe from the Nazi pestilence and saving the world from the new Dark Ages” was complete.

Of course, not every French home owned a radio set. And neither could every one that did own a set always receive BBC broadcasts. And so a ritual had emerged across the country, in villages and cities, where people gathered together—in homes, in the streets, around cafés, to listen to the evening broadcast at 8:15.

The authorities took note and enacted countermeasures. The first step was for the Germans to attempt to jam the broadcasts, but this was of limited effect because the BBC broadcasted on several different bands. The next step was for the Germans to order that in the occupied zone, citizens could listen only to broadcasts from its areas of control—Poland, France, Holland, Belgium, Norway, and the Reich. Vichy followed suit by enacting a law on October 28 that outlawed listening to the BBC and all “antinational broadcasts” in public places. One effect of these measures was to arouse greater interest in Radio London.

For those who were opposed to the armistice, who were suffering under the Occupation, who were terrified by the new exclusionary laws, and who were appalled by the regime’s expanding rapport with the occupiers, the news coming from London was the only source of moral support and hope. And to a small number, it was an inspiration to act.

ARMISTICE DAY

Léon-Maurice Nordmann was one of those who was very eager to do something to strike back at the Nazis. A successful lawyer at a young age, he had been politically active in the left-wing Socialist Party. Nordmann had opposed the Munich agreements and the policy of appeasement. When war was declared, he requested a place in a combat unit. He was very disappointed when, on account of his poor eyesight, he was assigned to the meteorological service. With his office in the plush Hôtel Georges V in Paris, Nordmann was frustrated and felt very guilty about serving in such comfort, just a short distance from his home, while others were off fighting the war.

Since his demobilization, Nordmann had been seeking out like-minded friends to see what might be done to rally against the occupiers. Very likable, a good conversationalist with an easy smile, Nordmann had a lot of very bright friends, including lawyer André Weil-Curiel and fellow music lover Jacques Monod.

Weil-Curiel served during the war as a liaison officer with the British Army and wound up being evacuated at Dunkirk. Stranded in England after the armistice, he immediately joined de Gaulle’s Free French. In late summer, he was sent back to France to gather intelligence on the situation in Paris and to promote the Free French. Once back in Paris, Weil-Curiel sought out Nordmann. They and a third lawyer, Albert Jubineau, formed a group they dubbed Avocats Socialistes (Socialist Lawyers). Their primary aim, and the aim of other nascent groups involving Paris’s intelligentsia, was to gather and spread accurate information about wha

t was happening inside and outside France. They hoped to build a clandestine organization that would recruit friends and colleagues and form links with other groups.

Monod joined Nordmann’s group in October 1940.

By early November, after the news of the Pétain-Hitler meeting, Weil-Curiel and Nordmann were wondering what it would take to provoke Parisians to begin to express their discontent. For their part, they were looking to make some public act of defiance against the authorities. Armistice Day, November 11, the day commemorating those who sacrificed and served in World War I, provided an ideal opportunity to arouse patriotic feelings.

There were rumblings about some form of demonstrations for the eleventh. The Young Communists organization in Paris disseminated a leaflet urging students to celebrate the memory of their fathers and brothers killed in the war. Another leaflet was spread among Paris high schools urging students to rally at the Place de l’Étoile at 5:30 p.m. The head of the police caught wind of the plans. On November 10, the newspapers carried an official notice: “Public organizations and private enterprises in Paris and the Department of the Seine will work normally November 11. Commemorative ceremonies will not take place. No public demonstrations will be tolerated.”

Radio London, however, thought otherwise. Maurice Schumann closed his program by urging all French people: “On the graves of your martyrs, renew the oath to live and die for France.” Another commentator added his appeal to veterans to maintain their hope, and to go to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and other monuments to pay their respects: “On November 11, to oppression and to cowards, you all say: NO!”

Meanwhile, Nordmann, Weil-Curiel, and friends ordered a huge wreath and made a three-foot-long calling card, wrapped in blue, white, and red ribbons. They addressed the card in large capital letters: LE GÉNÉRAL DE GAULLE. Before dawn on November 11, they put their tribute into a Citroën truck and drove through the empty streets to the Place de la Concorde, then up the Champs-Élysées to the statue of Georges Clémenceau, the prime minister who led France to victory in 1918. At 5:30 a.m., they quickly placed the wreath and the card at the foot of the statue and hurried away.

A good number of Parisians were able to see the card before a police patrol took it away. Word spread quickly about the gesture all over Paris. Throughout the day, citizens came to place more bouquets at the statue, as well as at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, at the statue of Joan of Arc near the Tuileries, and at a plaque near Notre-Dame that commemorated British sacrifices in World War I. The French police were generally accommodating and allowed the bouquets to be placed.

But late in the afternoon, as the school day ended, the mood changed. Students and teachers formed ranks and marched up the Champs-Élysées. Some carried a wreath shaped into the Cross of Lorraine, some wore red-white-and-blue ribbons. Some started to sing the verboten “Marseillaise.” Some shouted “Vive la France!” and “Down with Pétain!” The procession grew to several thousand people who started to pack in around the Arc de Triomphe.

The Germans were surprised for once—their orders had been defied. Around six p.m., armed soldiers on motorcycles, in trucks, and on foot hurried to the scene and began to disperse the crowd with clubs. Some students were beaten. Shots were fired into the air. The Germans closed off the streets and chased the marchers away from all of the monuments. More than a hundred people were arrested; some were taken to the Cherche-Midi and Santé prisons. Most would be released in the following few weeks.

The Germans were furious. The demonstrations were deemed “incompatible with the dignity of the German Army.” They closed the universities, required that every student register with the police, and dismissed the rector of the Sorbonne.

RESISTANCE!

Nordmann and Weil-Curiel were elated by the first show of defiance to the authorities since the Occupation began. They were immediately searching for other things they could do to rally opposition. The Avocats Socialistes were in contact with other groups. René Creston, a childhood friend of their comrade Jubineau, was part of another clandestine group that was organized around the Musée de l’Homme (Museum of Mankind). Organized by linguist Boris Vildé, anthropologist Anatole Lewitsky, and librarian Yvonne Oddon, the Musée group was focused on helping French and British soldiers evade the Germans and get to London, on gathering information, and on countering German and Vichy propaganda. Creston put the lawyers in contact with the Musée group, and the two quickly decided to work together.

The Musée network had in turn grown to include a group that called itself the Friends of Alain Fournier, a supposed literary club that wanted to spread information by establishing a clandestine press and distributing tracts in the occupied zone. The group included Agnès Humbert, art historian at the neighboring Musée des Arts et Traditions Populaires; Jean Cassou of the Museum of Modern Art; educator Marcel Abraham; writer Claude Aveline; publishers Albert and Robert Emile-Paul; Jean and Colette Duval, a teacher and writer, respectively; and Monod’s neighbors at 30 rue Monsieur-le-Prince.

Cassou was to be the editor in chief. However, they needed some way of printing and distributing many copies of whatever they put together. The Germans controlled the supply of paper and ink as well as all of the presses. Cassou made contact with Paul Rivet, the director of the Musée de l’Homme, who offered the use of an old Roneograph duplicating machine that had been stored in the basement. Rivet introduced Cassou to Oddon and Vildé, and Cassou in turn introduced Humbert to Rivet. It was decided that Humbert would be the liaison between the two groups.

Vildé warned Humbert of the consequences if the network was exposed. “Many of us will be shot,” he said, “and all of us will go to prison.” Humbert laughed, but he knew that Vildé was probably right. Life had already changed for several in the group: Cassou and Humbert were dismissed from their posts without any explanation in October, and Rivet was sacked from the Sorbonne and the Museum not long after the November 11 demonstrations.

The two groups decided to collaborate on putting out a newspaper that would relay the news coming from the BBC about the real state of affairs in France and overseas, and support de Gaulle. They called themselves the National Committee of Public Safety, and after some discussion they settled on naming the newspaper Résistance. The first page was to be written by Vildé, Lewitsky, Oddon, and others, while the next three were composed by Aveline, Cassou, and Abraham. Humbert was the typist; Lewitsky, Nordmann, Monod, and others volunteered to distribute copies.

The first issue appeared on December 15, 1940. The editorial read:

Resist! This is the cry that comes from the hearts of all of you who suffer from our country’s disaster. This is the wish of all of you who want to do your duty. But you feel isolated and disarmed … Resistance is here to speak to your hearts and minds, to show you what to do.

Resistance means above all to act, to be positive, to perform reasonable and useful things … The method? Group yourselves in your homes with those you know. Choose your leaders. They will find other groups with which to work in common … Find resolute men and enroll them with care. Bring comfort and decision to those who doubt or who no longer dare hope. Seek out and watch those who have renounced our country and betray it. Meet together every day and transmit information useful to your leaders … Beware of inconsequential people, of talkers, and of traitors. Never boast, never give yourselves away. Face up to the moment. Later we shall tell you how to act.

In accepting our responsibilities as your leaders, we have promised to sacrifice everything, staunchly and pitilessly, for this mission … We have only one ambition, one passion, one wish, to bring about the rebirth of a pure and free France.

AN HOUR OF HOPE

De Gaulle wanted to seize on the momentum of the November demonstrations and the simmering undercurrent of discontent. In order to further rally solidarity with his cause and to encourage more disobedience to the occupiers, he came up with an idea for New Year’s Day—a countrywide silent demonstration against the authori

ties. His spokesman Maurice Schumann broadcast the appeal on Radio London on December 23:

January first will offer to all French the opportunity to demonstrate that they are united in their grief and in their hope.

For the majority of French people, directly or indirectly repressed by the enemy, such a demonstration can only be silent. But, in accomplishing it in silence, it will only be more effective.

On January first, from two o’clock to three o’clock in the non-occupied zone, and from three o’clock to four o’clock in the occupied zone, all French people will remain in their homes and local shelters. All French people will remain indoors, either alone, or with family and friends. During this hour of contemplation, everyone will think together of liberation. This will be the hour of hope.

Everything should be done, everywhere, discreetly and firmly, so that this silent protest of our crushed country takes on an immense scope.

The second issue of Résistance appeared on December 30. The six-page paper summarized several months of developments: the rallying of colonies to the Free French, battles in North Africa, British bombings of Germany, Roosevelt’s reelection in the United States, Germany’s pillage of France’s economy, anti-Semitism, and more. A notice repeated de Gaulle’s appeal to remain indoors on January 1.

De Gaulle himself repeated the call on New Year’s Eve, with even greater force and optimism:

The hour of hope of January 1, during which no good French person will appear out of doors, wishes to say:

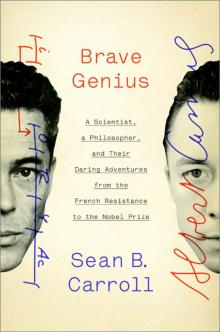

Brave Genius

Brave Genius